Nine cities have already signed on to the countywide utility, aimed at securing long-term water supplies without relying on state approval.

WISE COUNTY, Texas — At the end of June, Rhome’s only car wash shut down — not because of broken hoses, but because the water in the city ran low.

“It’s always the first to close when water runs low,” said City Administrator Amanda DeGan.

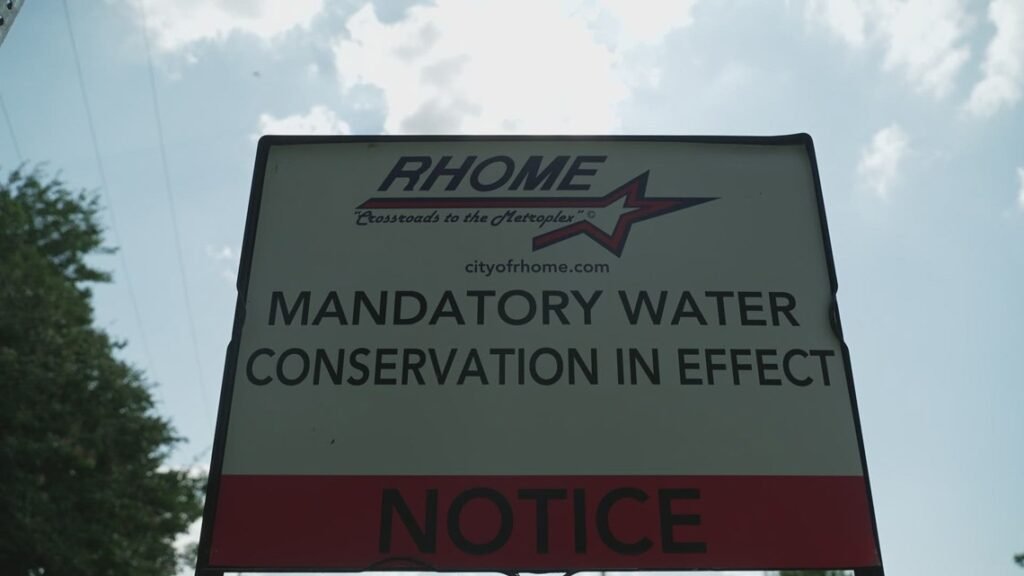

It makes sense, the business is non-essential–even if you have the dirtiest truck in town. Stage 4 water restrictions hit the city as summer began, and it wasn’t the first time.

“I’ve been here three years, and every summer we’ve had water restrictions,” DeGan said.

This year, there was a hiccup when the local utility district couldn’t deliver Rhome its full water allotment. The issue, however, reaches far beyond Rhome. Across Wise County, where 85% of residents rely on wells and no significant surface water is available, rapid growth has stretched the supply to its limits.

“We’re supposed to get 1,050 gallons a minute from Walnut Creek Special Utility District,” DeGan said. “But we haven’t been getting that yet because they’re still ramping up production.”

In other words, keepers of the pipeline can and have overcommitted and exhausted their capacity, she added. When restrictions hit, it begins with the town’s only car wash shutting down and people being told not to water their lawns, but if Wise County doesn’t find a long-term fix, the shutdowns won’t stop at the soap and suds.

Earlier this year, county leaders asked state lawmakers to approve a water district with the authority to tax, improve infrastructure, and tap new water sources. That bill failed.

“We’re not going to give up as far as bringing surface water into Wise County,” said Boyd Mayor Rodney Holmes.

Holmes testified in front of lawmakers and is leading the charge with the county’s mayoral coalition to find a permanent solution. On Wednesday night, county leaders gathered in Decatur with their fellow mayors, developers, and water districts to unveil a new plan: a countywide Public Utility Agency (PUA).

Unlike the failed bill, the PUA doesn’t require state approval. It won’t run on taxes; rather, it will be funded by water and wastewater revenue that’s already being collected by municipalities. It will focus on building infrastructure and securing new water supplies. Nine cities have already joined.

“It will be a long-term solution,” said Wise County Commissioner Kevin Burns. “It should be good for perpetuity.”

Part of that solution, officials said, is likely to involve drawing more water from Eagle Mountain Lake — which has a more abundant supply — instead of Lake Bridgeport.

For now, Rhome’s car wash is back open. But it still stands as a reminder: the county’s taps — and its future — depend on finding the next drop.